VOLUME ONE | ISSUE ONE

Wednesday, October 22, 2025

Welcome to The Game!

I am so happy to partner with Glenn Kaino, Toa Dunn, Alexys Feaster, Jesse Williams, and the entire VISIBILITY family for this exciting newsletter we are presenting to you.

Born out of and from work and conversations about gaming and the gaming industry, this space is also about the game of life, how we play it, how we learn, from our wins, from our losses, from each other.

Every digital issue will feature some of the leading voices from the worlds of tech, gaming, sports, politics, corporate, nonprofit, community, the arts, and social media influencers.

We want your spirit, your energy, too! Please let us know what you think, what you like, and what you want to see and hear and read. Because The Game is for all of us to play!

Kevin Powell, The Game Editorial Director, is a GRAMMY-nominated poet, humanitarian, author of 16 books, filmmaker, and writer of forthcoming biography of Tupac Shakur.

THE NEW RULES

What is GGS?

Glenn Kaino

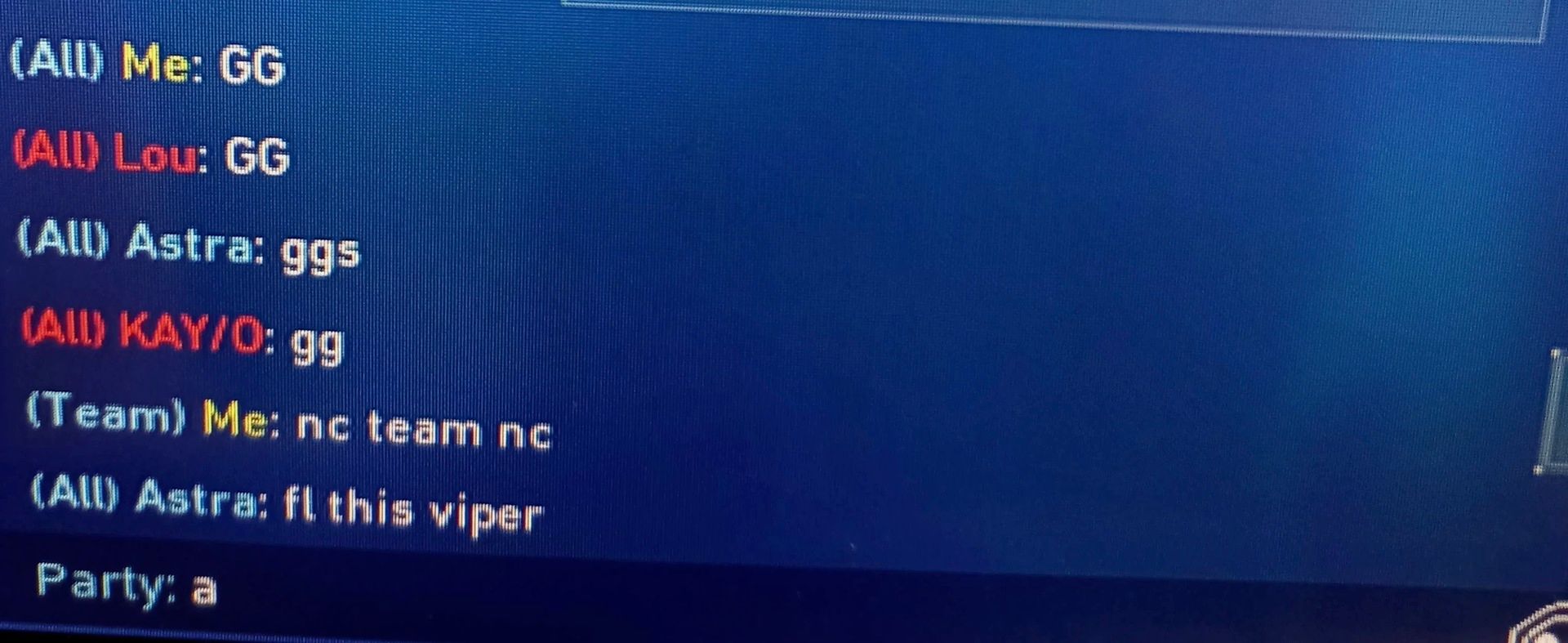

At the end of every multiplayer video game, it’s gamer etiquette to type those three letters—GGS—in the chat, or speak them into your mic. It stands for Good Games, though it is only plural because of multiple participants—they’re all talking about the same game. Win or lose, amazing performance or tragic, violently realistic shooting game or block building Tetris, everyone in the game honors the code. GGS. A tiny gesture at the end of a mostly meaningless competition.

But GGS might be the biggest lesson society can learn from gaming because at the heart of the gesture is the idea of de-escalation after a hard fought competition. It is an immediate, respectful way to conclude and compartmentalize a moment of dire competition and a way to mentally reset. The habit of saying it encodes the idea of sportsmanship into the fight before the fight even begins. You said it the last game and you’ll say it again. Let’s play again.

GGS is sorely missing in our world today. There are no universally accepted means of de-escalation like it. Rather, we’re seeing accelerated escalation of anger to the point of tragedy. No more handshakes, just more guns. GGS allows for the fierceness of battle with a social contract that we will all compete again. The game goes on.

Democracy is actually a game, each election is a round, and each round used to end with a form of GGS. The rules created by the founding fathers, nearly 250 years ago, were designed to be purposely difficult to win, so that sweeping victories would always reflect a large majority of the population. Now we’re constantly hacking, bending all the rules to eek out hollow wins at all costs that favor increasingly smaller player bases. GGS is not a rule but a tacit agreement to even play. We need to make sure the game goes on.

Non-gamers often discount the relevance of video games to society but regardless of their rejection, gaming is here to stay. Perhaps if the only good thing we all learn is to remember GGS, video games might actually have the power to move society forward in unpredictably positive ways by reminding us that there's always another round.

Glenn Kaino is a conceptual artist, director and life-long gamer, who was better at FPS games before movement error was introduced.

GAME TIME

The Game of LoyaltyToa Dunn

Every time I pull my wallet out, I can’t help but think that this feels too familiar. The swiping of the card, the increase in reward points, and the satisfaction of getting closer to diamond status. I wouldn’t consider myself someone who enjoys shopping, but I do find myself making exceptions if it helps to move the blue indicator closer to my status goal. Current Quest Progress: DIAMOND STATUS

Delta Airlines once reported a six-billion-dollar loss, yet their loyalty program generated twenty billion in revenue. Starbucks Rewards members account for 57% of their revenue (in the U.S.).

At the heart of it all this is a familiar design: video games. And this game is called “consumption,” and we’re all players. The Game LoopEvery game is built on a game loop, a repeating cycle that keeps us engaged. We are often participating in a game loop, even if we don’t realize it. There are 3 key indicators in recognizing a game loop:

1

Action

We, the player, perform a specific task. In darts, you throw. In shopping, you spend. The desired behavior is clear and measurable, companies have simply replaced “throw the dart” with “swipe your card.”

2

Rewards

Success triggers a reward. In darts, you score points. In loyalty programs, you collect points. The more you buy, the more you’re told you’ve “earned.” Every transaction feeds the loop.

3

Progression

To keep us coming back, games will offer long-term goals. Keep scoring points to win the game, or earn enough points to unlock a higher membership tier, and gain new perks. It’s the same dopamine hit as leveling up in a video game.

This structure of action, reward, progression, is one of the most effective behavioral systems. It’s why the global video game industry, worth $185 billion, outpaces both music ($29 billion) and film ($100 billion) combined. And here’s the twist: unlike most games, this one never ends. There are no rounds, no final boss, no “Game Over.” The consumption loop runs 24/7, recharging with every sale, discount, and flash offer designed to trigger your next move. All we have to do is play.

Toa Dunn is a visionary and strategic leader that has redefined the relationship between music, culture, and video games.

|

Why Black Folks Love Taboo

Evangeline Lawson

Taboo is up there with Spades and Uno for Black folks. It’s a game that can swiftly bring on action, conjure competition, and, if not careful, end in conflict. But those things are what makes us pull out the cards and buzzer at functions. It’s not necessarily a game of extreme strategy, but of word play, which is an incredible gift many Black people have.

Taboo is where you break into teams and get your partners to guess a primary word using clues. You cannot use certain related words. If you do, you get buzzed and lose that card. For example, if you’re trying to get people to guess the term breakfast, then they’d probably exclude expressions like morning, pancakes, toast or bacon, leaving the clue-giver to rely on creative phraseology. To add pressure, there is a timer. The goal is to get as many cards correct in each round and crown a winner based on who has the most overall.

Black people love Taboo because it's not only a test of linguistics, but ingenuity. It’s the ultimate measurement of your ability to codeswitch.

When our ancestors were kidnapped from Africa and enslaved in other parts of the world, one of the first things to be stripped away was our language. We developed a unique blend of vocabulary that was innate to us and mixed with the idioms of our colonizers. Patois, Creole, Gullah were beautifully crafted out of those circumstances along with African American Vernacular English, all of which are still used today. These adaptations have been a means of connection, survival. Additionally, a legacy of storytelling and speaking in rhyme have reinforced the value of developing a vast lexicon, combining intelligence and wit. Those who are meant to get it, successfully do, while the ones who cannot decipher the messages, are left out.

Often, Black people have to defend against our dialects being viewed as evidence of a lack of intelligence.

Taboo is one of those spaces where we can demonstrate the opposite. Because we have the advantage of straddling two worlds. So if I pull the card to get my team to guess breakfast, I can say “Big Mama always made this for us before church” or I could say words like “grits” and “biscuits”, but I could also say “quiche” or “fritatta” or “ackee and saltfish” and confidently know that someone would definitely yell out “BREAKFAST!”

Evangeline Lawson is a multi-media storyteller who loves preserving the culture through writing, photography and filmmaking. Her work can be viewed on her website https://www.evangelinelawson.net/

LEADERBOARD CHAT

|